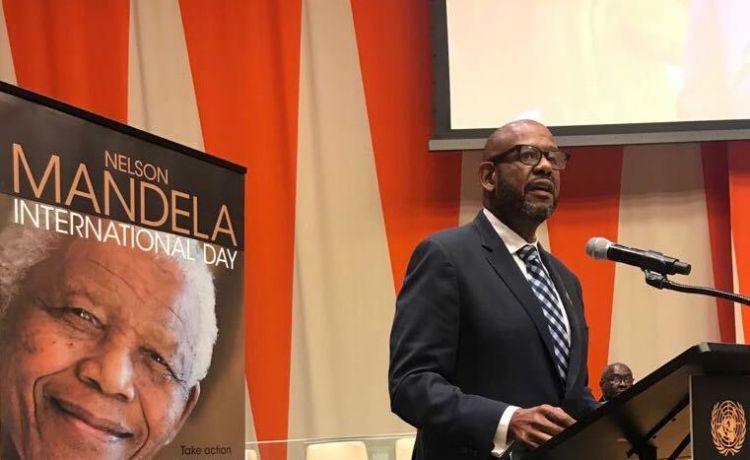

A Blog Post by Forest Whitaker

Freedom is probably one of our most precious properties, one that actually conditions the use of all our properties: even our very selves, both body and mind. This is why the protection of our freedoms is almost always the first priority of a decent government. When we look back to the 20thcentury today, it’s almost outlandish to consider that governments would deprive people of freedoms not because they committed crimes or infringed on the freedoms of others – but because they were born to a certain group. And yet, these political regimes have existed. In South Africa and the United States, it took the courage of citizens – both black and white – to denounce and eventually overthrow the racist architecture that legalized the violation of human freedom. Freedom Day celebrates this history, but it is not a mere commemoration of the past. It is an invitation to transform the present and build a better future.

When I look back to the years that preceded the demise of the Apartheid regime, I am always struck by the fact that this was a war where many of the foot soldiers were children, adolescents, and young adults. They lived in townships, places with no future. They were told that inequalities were part of daily life. Still, they refused to believe it. Their determination to break the shackles of tyranny impressed the world. The thirst for freedom is universal, but I know that it is especially strong in youth. This energy should be admired, and is energy that we must tap. With my foundation, the Whitaker Peace & Development Initiative (WPDI), I strive to empower young people from conflict and violence affected communities to become community leaders, entrepreneurs, and teachers. We are active in a wide range of contexts: war-scarred regions of South Sudan, refugees and former child soldiers in Uganda, gang ridded neighborhoods of Tijuana and indigenous communities of Chiapas in Mexico, and the Cape Town Flats in South Africa. These places are quite different from one another, and the people there face very distinct challenges. Yet, we have seen a commonality among them: they all possess cohorts of young people determined to make a difference, to imagine a future that is better than the present. The young people I work with mostly come from very difficult backgrounds, where youth are often considered to be either victims or perpetrators of violence. I see another way: they can be the ones engineering peace.

Mandela’s actions helped me to develop this approach, and I believe that he captured the idea perfectly when he said: “to be free is not merely to cast off one’s chains, but to live in a way that respects and enhances the freedom of others.” In essence, we are all made freer through working for the freedom of others. Based on this, I see my mandate as a rather simple undertaking: channel resources to these youth so they can be empowered to bring positive change into their communities. These resources come in different forms, including grants to create social businesses, but mostly boil down to skills that the youth can mobilize for years or decades in the service of others. Having done this for nearly ten years now across five countries, I can tell that this is a very effective approach. My criterion for success is, again, rather simple: the young leaders that we train and support are regularly enrolled by local leaders or even international organizations to perform sensitive activities on their behalf.

2020 included an example of these activities, as local leaders in the Flats requested our youth to organize workshops that would sensitize residents to the issue of gender-based violence, an issue that disproportionately targets women. This was in response to the surge of domestic violence that resulted from the COVID-19 pandemic’s confinement. Gender-based violence is a key issue – one that the President of South Africa, Mr. Cyril Ramophosa, has made a national cause. And indeed, pervasive violence and insecurity are a massive burden on our freedom: both the freedom of women, and by extension, the freedom of children and people at large. Mobilizing young people to combat gender-based violence is only one example of what can be done to magnify their freedom. This concept is one that can be generalized and taught as a defining pillar of citizenship; we cannot be free in isolation. If we value our freedom, we must also value the freedom of others, and work to achieve it. As we consider the role of freedom, our most precious property, we must also consider Mandela’s lesson; despite appearances, freedom is not a personal property. Freedom is a collective property, to which we’re all responsible.